“Fungi are precious treasure, invaluable for the survival of our species.” Fungarium Curator Lida in Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

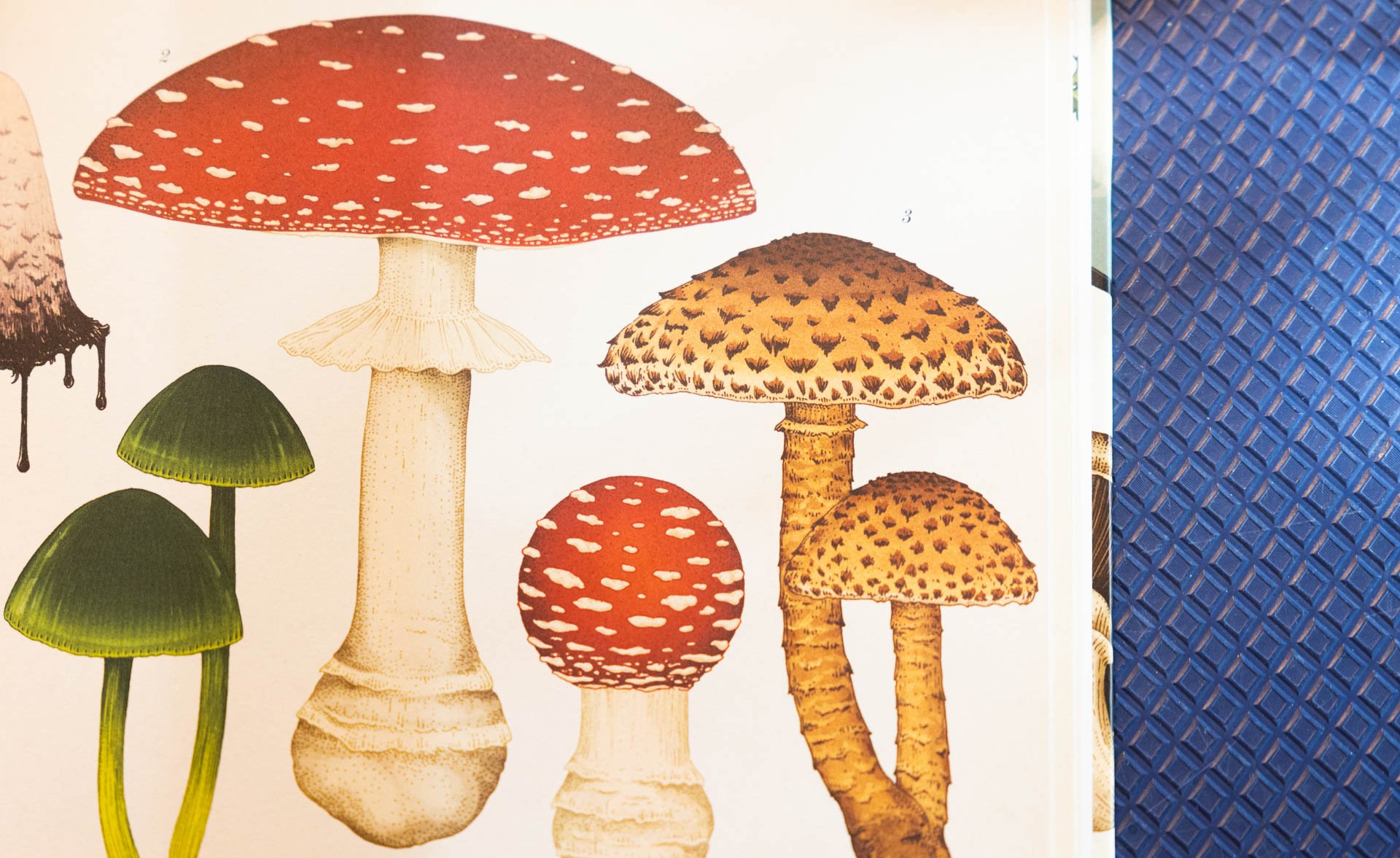

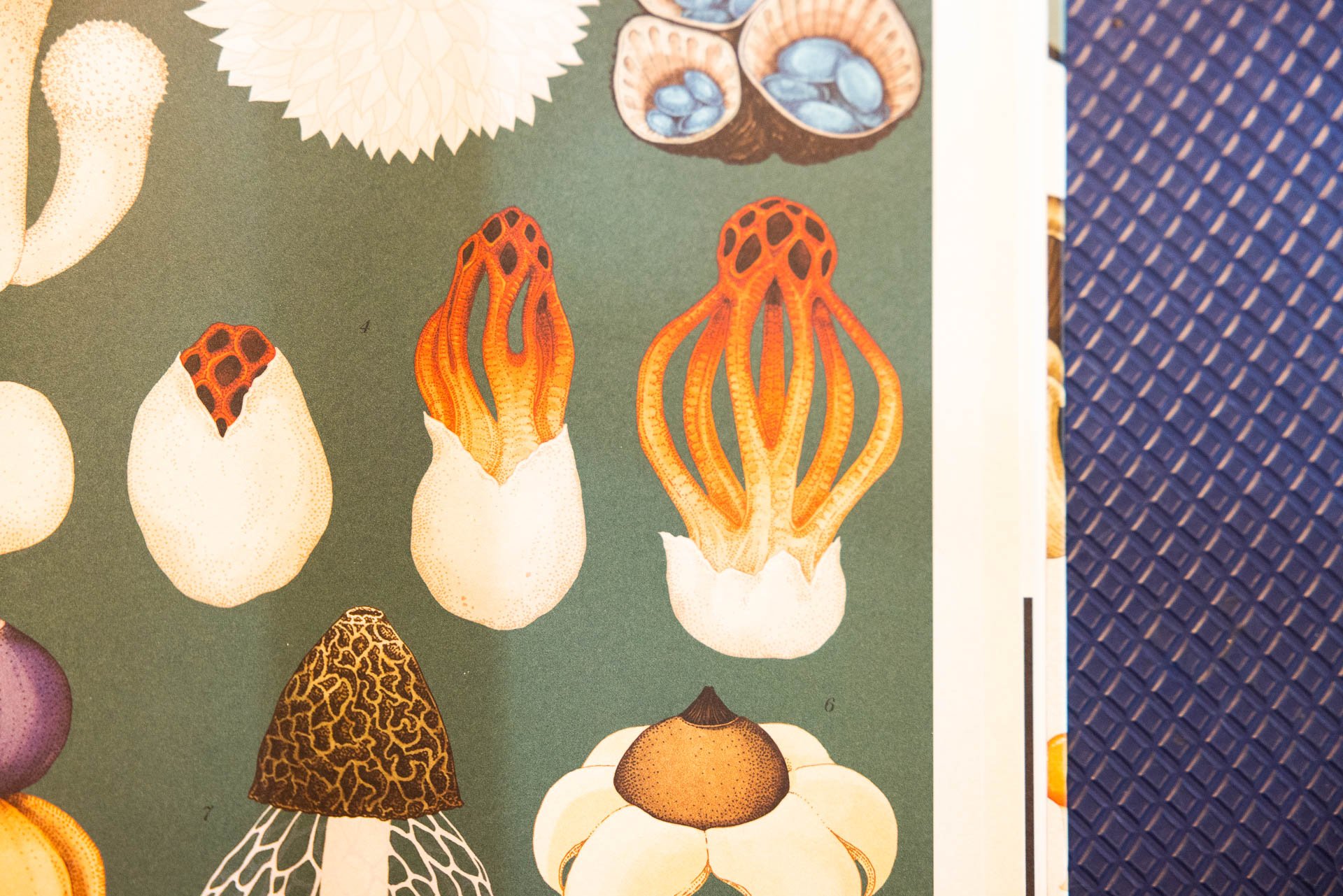

Year on year, abundant colourful specimens pop up from the ground. Once you notice them, fungi seem to appear everywhere in a vast variety of shapes and sizes, luring you in to take a closer look. Their vibrancy elevates them from the familiar mushroom we all know well.

Billions of years ago, these structures were one of the first complex life forms on land, creating life on earth as we know it today. It’s not a coincidence that human beings share a significant proportion of our DNA with fungi. They are closer in structure to animals than plants.

Fungi are at the heart of our cycle of life, from the first awakenings of our existence to the vital decomposition of our structures when we die. Beneath the ground, the fungal network of mycelium helps the roots of plants to flourish, creating a thriving ecosystem.

There is something undeniably special about fungi that begs further discovery. That’s why we’re on a mission to meet a fungi guardian and expert, Lida, the Fungarium Collections Curator at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

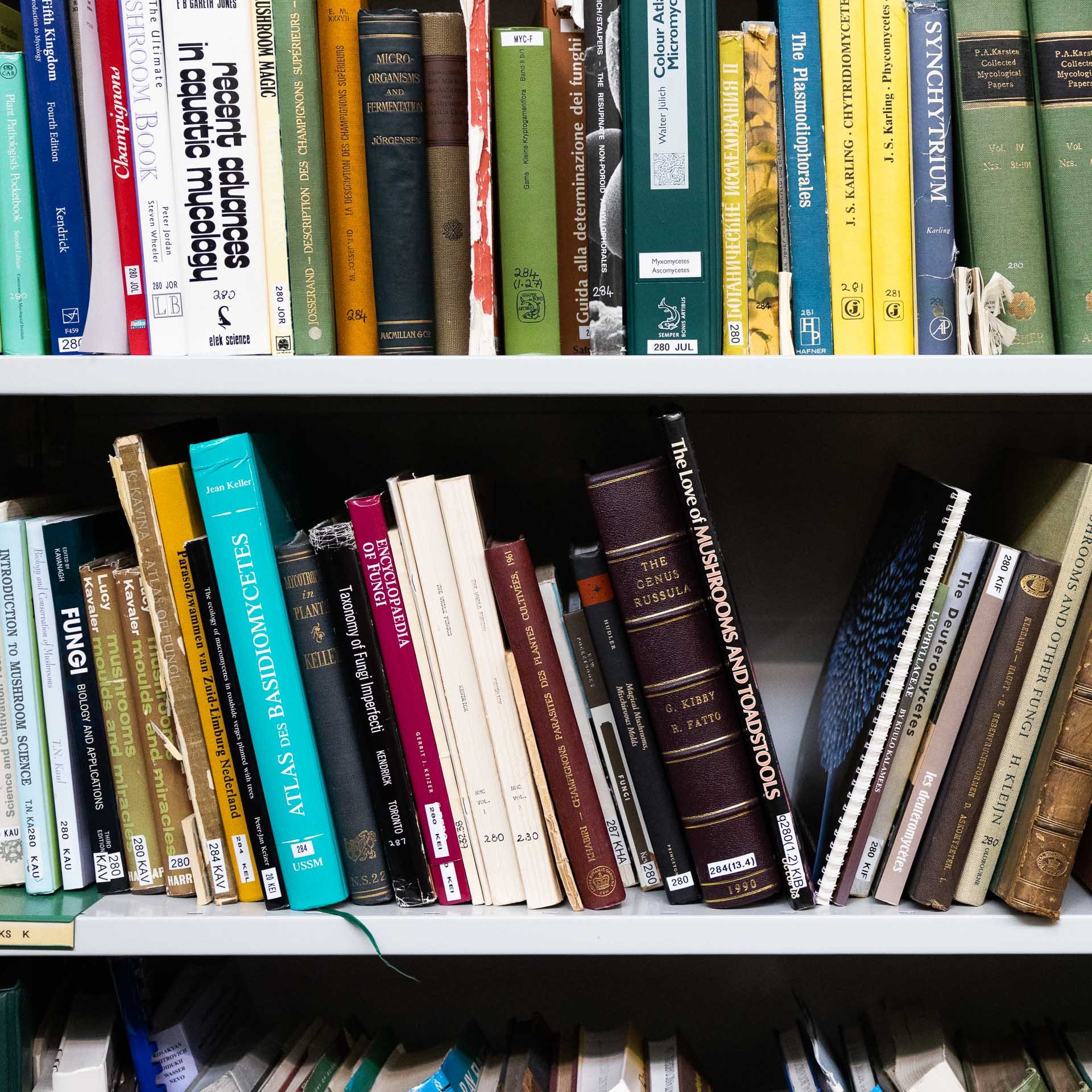

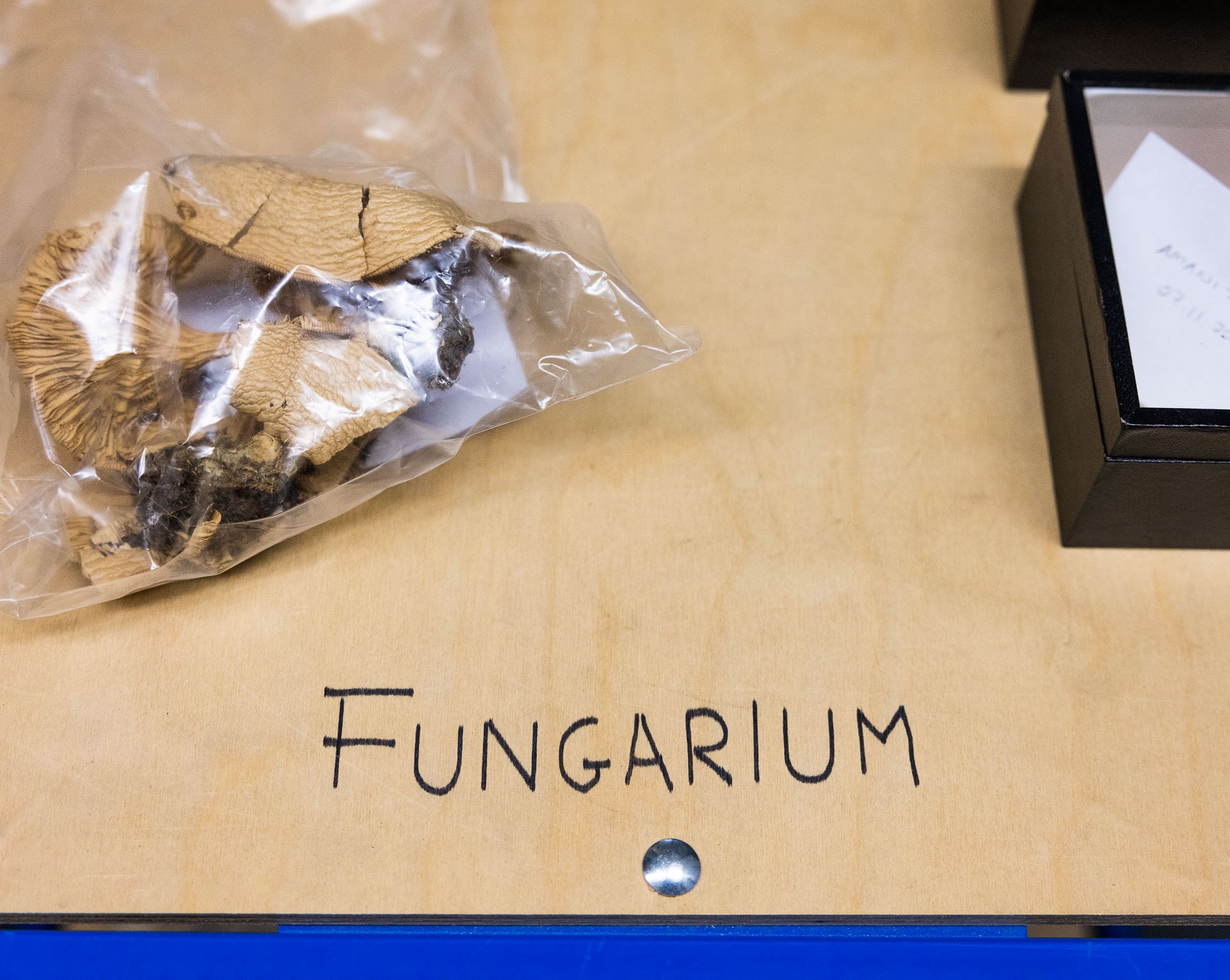

After being led along a series of corridors and downstairs, we enter an expansive room where Lida is sat at her desk, surrounded by stacks of papers, books, and eye-catching fungi bunting. All around are countless shelves, as high as the ceiling, with boxes in a distinctive lime green shade.

Resisting the urge to open the closest box, we sit down to hear about how she came to work in one of the most scientifically important collections of fungi in the world.

“Nature and I have always been inseparable. Where I grew up in Bangladesh, I used to buy plants instead of chocolate with my pocket money. I would spend hours as a child watching cloud formations, and stars at night, and storms gathering in the sky.”

Lida describes how her childhood enabled her to explore and enjoy the natural world. Near her parents’ garden, she discovered parasol shaped structures, the first encounter with fungi that sparked her imagination.

This curiosity fuelled her to later study plants in different forms: a BSc in agriculture and an MSc in entomology in Bangladesh, followed by an MSc in biological sciences in London.

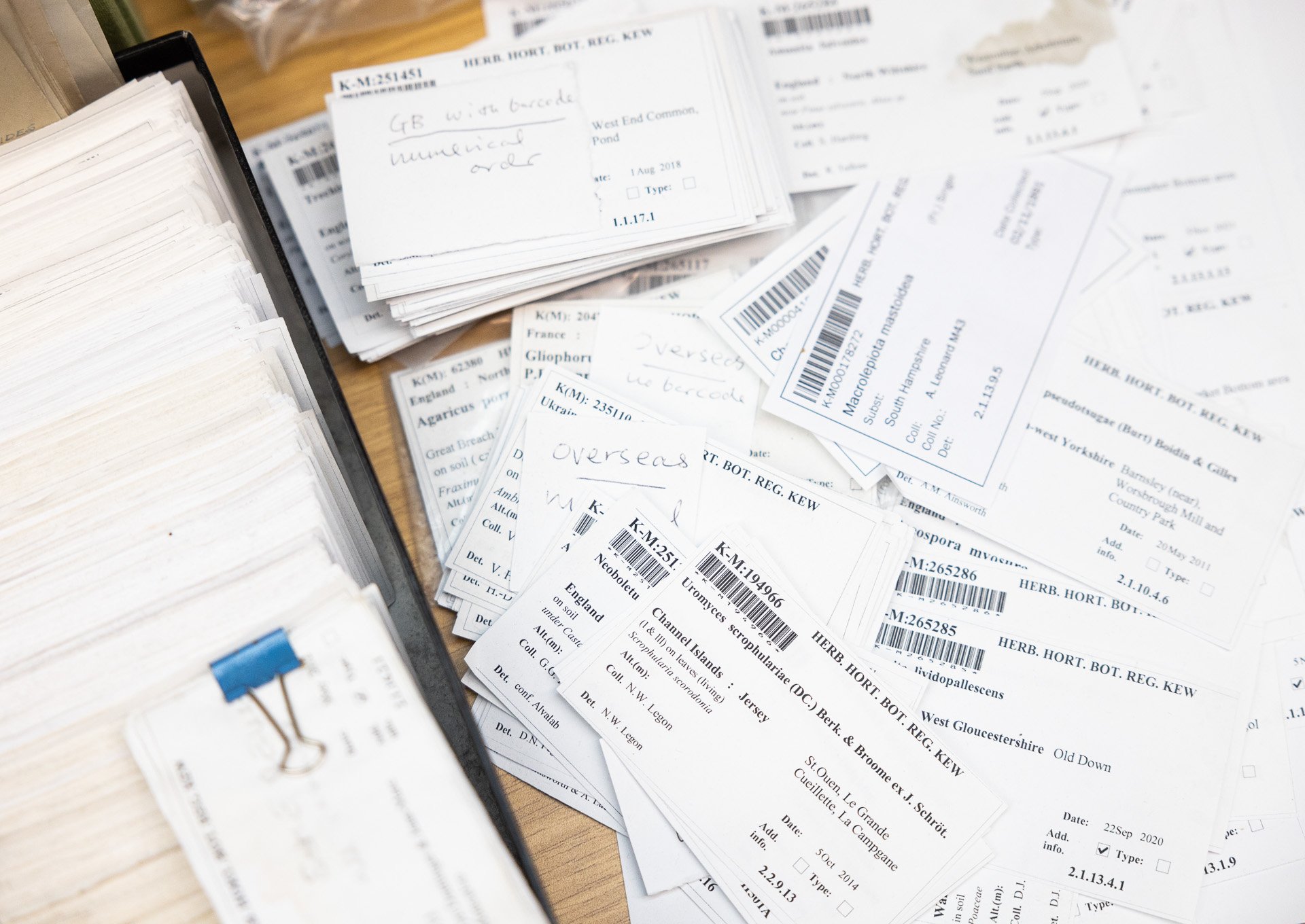

Transitioning from a more academic role to becoming Fungarium Curator at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, she handles the fungi specimens brought to her, drying, labelling, and databasing them.

Her in depth knowledge of the vast collection of 1.25 million dried specimens is essential. Lida has a clear mind map of the whereabouts of all the fungi. This incredible headspace seems to mirror a mycelium network, intricate and carefully balanced to make the whole system work.

A particular quirk of handling dried fungi is the shock and delight she experiences when they appear in the wild and she gets to see their colours for the first time, bringing on goosebumps.

Lida often takes her lunch break in places where a ring of capped fungi will appear in October, a poignant association between her work in the Fungarium and the gardens nearby.

“When I first came here, it was like entering my version of heaven. I believe this is paradise. I saw the daffodils and magnolias in bloom and the Japanese garden, and then working here with the fungi all around me every day is a dream.”

Her relationship to fungi has shifted since she was younger, from simple enjoyment to a deep sense of respect, now knowing their crucial importance to humanity.

Fungi have medicinal and nutritional value. They are shown to lower cholesterol levels and form the basis for medicines, as well as being key to recycling nutrients in ecosystems, through their digestive enzymes that break down plants.

Lida is cautious about the risks of over-foraging fungi, such as in Epping Forest where they no longer grow because too many people have picked them. At Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, she values the emphasis on sustainability, including training workshops that are run around the world on fungal conservation.

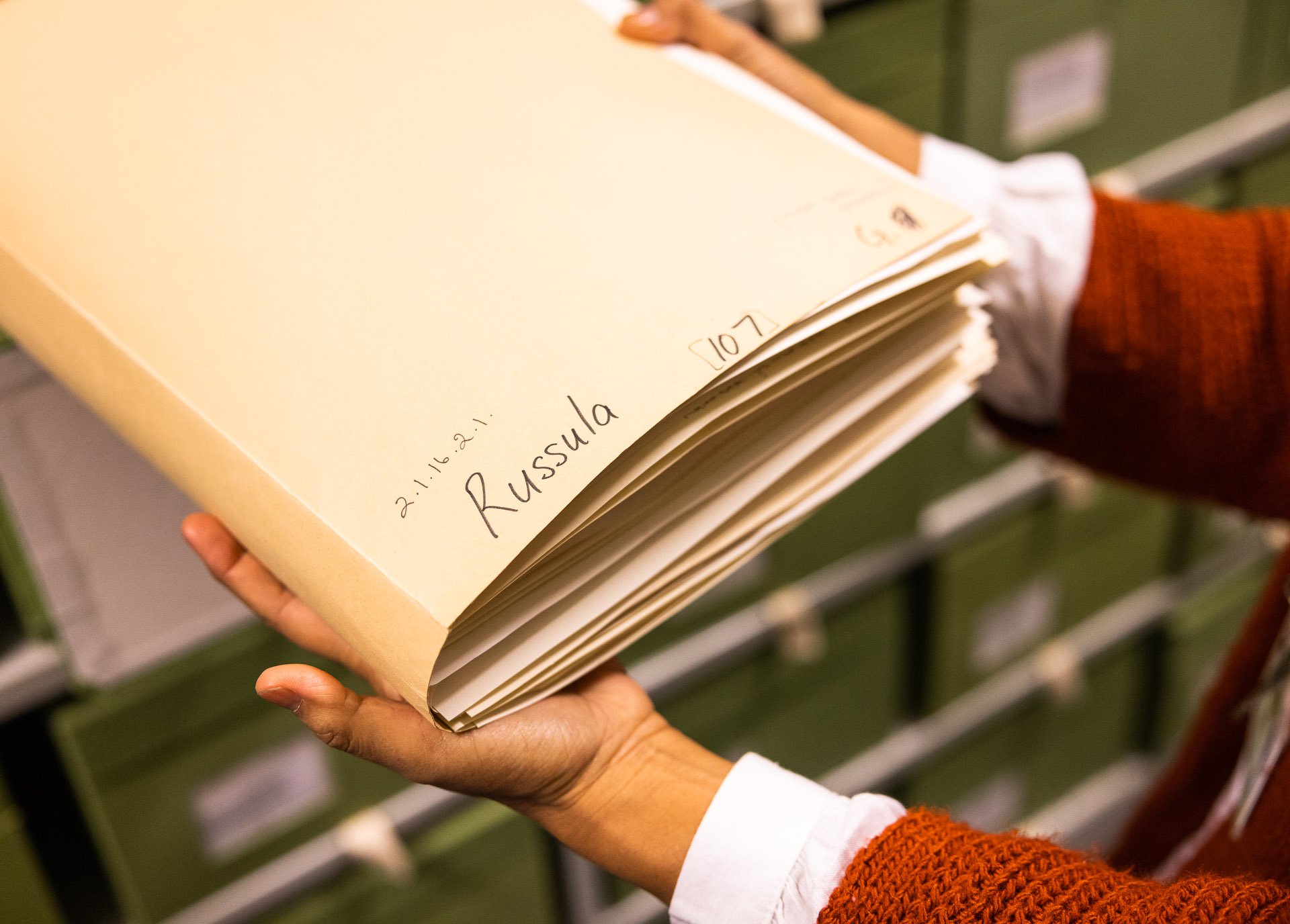

We walk over to enter the labyrinth of specimens to see some of them for ourselves. Lida’s orange cardigan and red lipstick compliment the sea of green as she carefully pulls out various boxes and pulls out the folders containing the fungi to show us.

Each specimen is catalogued, and Lida points out the extensive work that goes into collecting each one from the far reaches of the world before it ends up in her hands. You can already feel the richness of the fungi network distilled in this room.

“When I first open a new box, the first thing I’ll see is history behind it and the taxonomic name of the fungus. The label tells me where the mycologist has gone to collect it. Often local people in remote areas are involved in the search. It’s not as simple as going to pick a fungus, each time, it’s a crucial mission to gather a specific specimen for future study.”

Lida feels an even greater responsibility knowing about these excursions. Particularly looking at old specimens from hundreds of years ago, she marvels at how they were able to find rare fungi without technology to help guide them.

In her spare time, she travels widely, always finding new places across Britain in the outdoors to explore. Her adventurous spirit means she is particularly invested in preserving these small pieces of the natural world from so many different places.

Coming from Bangladesh, she also has first-hand experience of transitioning from one country to another, the joy of discovering a new place, and some of the challenges this can pose.

Encouraging people from different backgrounds to work in prestigious academic spaces provides a richness of experience, but diversity isn’t always easy to achieve. Lida describes her own journey.

“To be honest, it wasn't easy. I had to study for many years, and my education wasn't as valued in the UK as in Bangladesh. I had to learn how the workplace works here, because I came from a completely different culture. I did a lot of volunteering in many different organisations, such as the Natural History Museum.”

“It's been a long journey for me personally, but I feel like things are getting better in terms of diversity. After working at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, r the last twelve years, I’ve seen more people from the Asian Indian subcontinent come to work here.”

“I think it’s all about creating opportunities for people from minority ethnic backgrounds, helping them overcome language and cultural barriers to achieve brilliant things if they care about nature.”

Lida’s resilience and compassion has led her to where she is now, such a dedicated custodian of the Fungarium collection. You can tell how much she cares about the plants and fungi, which makes her the perfect curator. Her passion can inspire others from different countries or backgrounds to follow in her footsteps.

We inspect some of the specimens Lida has laid out. When dried, fungi look like sea creatures, with tentacles dangling from them. One specimen is so large it could be mistaken for a chunk of wood, while another has small white spots on its cap.

The diversity of fungi is reflective of our human experience, each of us with our unique characteristics to be valued and nurtured.

Lida explains that a tiny proportion of the world’s fungal species have been properly researched and documented, a mere 7%, leaving the vast majority undiscovered. The potential natural powers that the specimens in Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, hold is unimaginable.

“Fungi are precious treasure, invaluable for the survival of our species. These specimens are so important for future study and identification by mycologists. Due to climate change, many species might become extinct, including fungi. Every specimen here has the chance to save us in future. When I hold each one, it feels valuable.”

She is determined to save them before it’s too late, to preserve the fungi in this vast treasure trove. Lida’s calling to nature from an early age has given her a much greater purpose now, something she hopes to pass on to the next generation.

“My son has always been interested in nature and seems to follow in my footsteps. Recently, he was on a walk with a friend who pointed out some mushrooms and my son immediately corrected him, saying ‘no, those are fungi’.”

If young people like him gain knowledge about nature, collections like those at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, will continue to be the centre for pioneering research.

The fungal cycle relies on a steady rhythm of birth and decay, that has been happening for millions of years. With climate change, this could be stopped in its tracks as ecosystems are already being thrown out of balance from unpredictable seasons and the abundant plants are diminishing.

Lida believes that we can all find a way to prevent this from happening. As she carefully packs away the fungal specimens back into their box, you can tell that they are in very safe hands.

“To tackle climate change, everyone needs to spend time outdoors, in the mountains, by trees, on riverbanks. We need to take a deep breath and feel the positive energy, to open our eyes to what is all around. Nature is so precious, and each of us must play our part to protect it for the future.”